Markov Text Generator in Dunaj

I recently needed a simple and straightforward mechanism to generate a bunch of genuinely looking sentences. I ended up using Markov Chains and as I had lots of fun with it, I’ve decided to write a post about Markov Text Generator and its implementation in Dunaj.

| Dunaj is an alternative core API for Clojure. If you are new to Dunaj, please check out its homepage and a crash course for Clojure developers. |

In this post I give a quick introduction on how Markov Chains are used to generate random sentences. Then I will walk through the implementation of a sentence generator in Dunaj and at the end I have prepared a small game, where you can guess the source novel for generated sentences.

Markov text generator

The usual definition of Markov chain is that it is a discrete-time stochastic process with finite states where the probability of the next step depends only on the current state. The previous states do not influence the transition probability in any way. This feature of Markov chains is called a Markov property.

Markov Chains are often used to generate text which mimics the document that was used to generate the respective Markov Chain. These Markov Text Generators are quite enjoyable to develop and work with, as they often produce hilarious results. As an introductory example, lets take the following old poem from The Nursery Rhyme Book to generate Markov Chain.

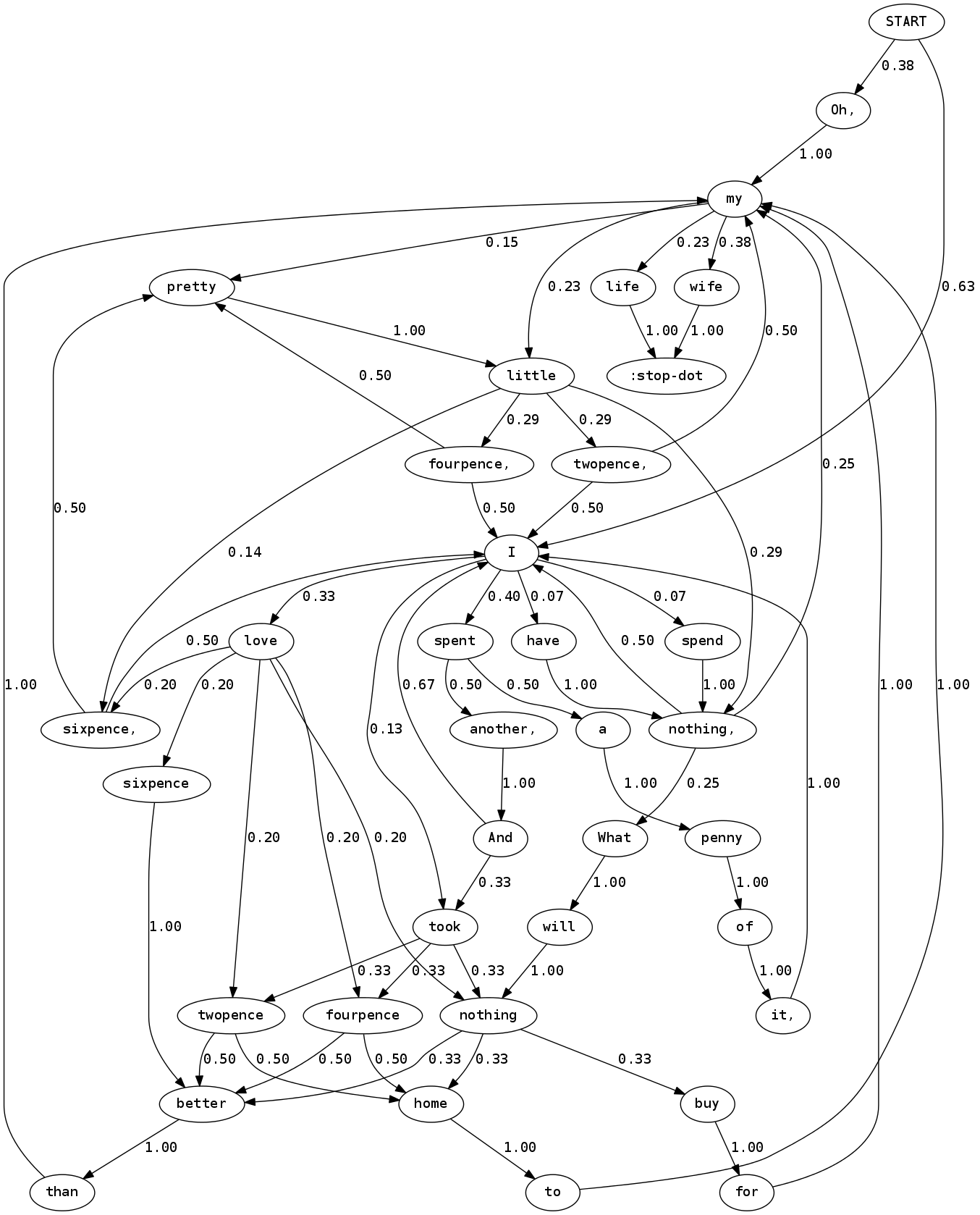

I love sixpence, pretty little sixpence, I love sixpence better than my life. I spent a penny of it, I spent another, And took fourpence home to my wife. Oh, my little fourpence, pretty little fourpence, I love fourpence better than my life. I spent a penny of it, I spent another, And I took twopence home to my wife. Oh, my little twopence, my pretty little twopence, I love twopence better than my life. I spent a penny of it, I spent another, And I took nothing home to my wife. Oh, my little nothing, my pretty little nothing, What will nothing buy for my wife. I have nothing, I spend nothing, I love nothing better than my wife."

The Nursery Rhyme Book

Input text is parsed into a sequence of tokens, such as words. Adjacent tokens define transitions from one state to another, where token serves as an identifier of a state. There is one starting state and usually there is a set of special tokens that denotes the end of a sentence.

The above poem has 674 characters, and consists of 128 tokens, 35 of

which are unique. The resulting Markov Chain will thus have 35 states.

Tokens with the largest number of unique transitions are I, love,

little and my. Each transition is assigned a probability based on

how many time this transition was found in a sample text compared to

other transitions for a given state. Following graph (generated with

rhizome) shows the complete

Markov Chain:

To generate random sentence from a Markov Chain, the generator begins at a starting state and walks through the graph according to given transition probabilities, until it hits one of the ending states. The recorded sequence of states will form the contents of the generated sentence.

Sentences generated from Markov Chain mimic the source document, but are often nonsensical, and the generator may cycle for quite a long time before it ends. But sometimes the generated sentences are genuinely looking and even quite amusing. Following list shows examples of sentences generated from above Markov Chain:

-

"Oh, my life."

-

"I spent another, And took fourpence home to my wife."

-

"I love fourpence better than my wife."

-

"I spend nothing, my little fourpence, I spent a penny of it, I spent another, And I spent a penny of it, I spent a penny of it, I spend nothing, I spend nothing, What will nothing better than my little fourpence, I love sixpence, I took nothing home to my little fourpence, I spent a penny of it, I love nothing home to my little nothing, What will nothing buy for my wife."

Implementing Markov Chains

The implementation of Markov Text Generator can be divided into four parts; fetching the sample data, parsing it into a sequence of tokens, the construction of Markov Chain, and the generation of a random sentence.

The complete source code can be found at dunaj-project/try.markov repository, in the markov_naive.clj file.

| In order to keep the code in this tutorial short and understandable for newcomers, many performance improvements are omitted. |

Sample text

For this tutorial, we will be using Melville’s famous novel Moby-Dick as a source document for the construction of Markov Chain.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

(def text

(with-scope

(str (slurp (classpath "try/document/moby_dick.txt")))))

;;=> #'try.markov-naive/text

(count text)

;;=> 1210052

(pp! text)

;; "Call me Ishmael. Some years ago--never mind how long precisely--having\r\nlittle or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on\r\nshore, I thought I would sail about a little and see ..."

The above code loads the contents of the file into the string and queries the size and the first few words of the loaded novel.

-

As the file is placed on a project’s classpath, we are using Dunaj’s

classpathfunction to acquire resource for this file. For resources that are stored on a local filesystem, afilefunction should be used instead. -

The

slurpfunction in Dunaj must run inside an explicit scope, so that no resources are leaked. -

Dunaj’s

slurpreturns a collection recipe instead of a string, so we also need to callstrexplicitly in order to load whole file into memory and represent it as a string. In practice, we would process the result fromslurpdirectly without the intermediate conversion into the string, which would give us a boost in performance, would use less memory, and would enable us to process arbitrarily large data.

Word tokenizer

In the next step, we need to transform a sequence of characters into the sequence of tokens. Dunaj provides dedicated facilities for data formatting, that include parser and tokenizer engines.

Dunaj’s tokenizer engine uses parser machine factory to dispatch items of the input collection of characters into a collection of tokens. The following snippet of code shows the definition of a word tokenizer machine factory that will be used to parse our text:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

(def word-tokenizer

"A tokenizer machine factory for words."

(reify

IParserMachineFactory

(-parser-config [this]

{})

(-parser-from-type [this]

(keyword->class :char))

(-dispatch-tokenizer [this config state item]

(cond (word-char? item) (word-token item)

(= item \.) :stop-dot

(= item \!) :stop-bang

(= item \?) :stop-qmark

:else this)))

Termination characters are transformed into keyword tokens, and

a word-token function is used to construct a tokenizer machine

that will extract one word token from the input. As Dunaj’s

data formatting facilities are focused on performance, the

implementations of tokenizer machines will be given their input

in form of a host specific low level data containers, called batches

(in JVM they are implemented as NIO Buffers). Batches are mutable containers

and must be handled in a less functional way than the rest of the

code. The added benefit is the very efficient processing, that

can handle large amounts of data very efficiently, both in terms

of speed and memory use.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

(defn ^:private word-token

"Returns new instance of word tokenizer machine that contains item."

[item]

(let [word-ref (atom [item])]

(reify

ITokenizerMachine

(-analyze-batch! [this bm batch]

(loop [c (next-char! batch)]

(cond

(nil? c) this

(word-char? c) (do (alter! word-ref conj c) (recur (next-char! batch)))

:else (do (unread-char! batch) (str @word-ref)))))

(-analyze-eof! [this] (str @word-ref)))))

The actual parsing is performed with tokenize-engine function which

returns a collection recipe that contains parsed tokens. Note that

tokenizer-engine fully supports transducers and will return one

when no collection is given. The following code shows the actual

parsing and the examination of resulting collection.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

(def words (tokenizer-engine word-tokenizer text))

;;=> #'try.markov-naive/words

(count words)

;;=> 221634

(seq (take 45 words))

;;=> ("Call" "me" "Ishmael" :stop-dot "Some" "years" "ago" "never" "mind" "how" "long" "precisely" "having" "little" "or" "no" "money" "in" "my" "purse," "and" "nothing" "particular" "to" "interest" "me" "on" "shore," "I" "thought" "I" "would" "sail" "about" "a" "little" "and" "see" "the" "watery" "part" "of" "the" "world" :stop-dot)

Markov Chain

For the actual representation of a Markov Chain, a persistent hash map will be used. First we create a collection of transitions and then we will use this collection to construct a map, that will have a following structure:

1

2

3

{"foo" ["bar" "baz" "bar" "bar"]

"bar" [:stop-dot "foo" "foo"]

"baz" ["foo" :stop-dot]}

Keys in the map represent the state of a Markov Chain and the vector of tokens associated with a given key denotes all possible transitions from that state. Token may be included more than once, which reflects its probability to be used as a next state. The actual implementation is pretty straightforward:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

(defn assoc-transition

"Returns markov chain with cur->nxt transition added."

[chain cur nxt]

(let [key (when-not (keyword? cur) cur)

vals (get chain key (edit []))]

(assoc chain key (conj! vals nxt))))

(defn markov-chain :- {}

"Returns markov chain, in form of a map, from given collection of words."

[words :- []]

(let [transitions (zip (cons :start words) words)]

(reduce-unpacked assoc-transition {} transitions)))

Here we are using multireducible features of Dunaj, creating

convolution of two collections with zip and using reduce-unpacked to process the

multireducible without creating any intermediate pairs of values, that

would be needed if we have used a classic reduce. In fact throughout

the whole process, no intermediate collections or lazy sequences were

created, as zip also does not create any temporary collections.

Also note that in order to speed up the construction of markov chain,

a transient vectors are used to represent possible transitions for

a given key. Now that we can create markov chains, let’s create one

and inspect its contents a bit:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

(def mc (markov-chain words))

;;=> #'try.markov-naive/words

(count mc)

;;=> 23453

(seq (take 20 (keys mc)))

;;=> (nil "shouted," "convince" "weary," "Lower" "mounting" "howled" "posse" "declares," "shelf," "heaped" "new," "rainbow" "Bartholomew" "in," "blandishments" "Christianity" "absorbed," "float" "sweet")

;; number of different starting words

(count (distinct (mc nil)))

;;=> 1763

;; see possible successors for "Ishmael" state

(seq (mc "Ishmael"))

;; (:stop-dot :stop-dot "can" :stop-dot "hope" :stop-qmark :stop-dot "but")

;; some more insight

(let [s (vec (sort-by #(count (second %)) (vec mc)))

pf #(->vec (first %)

(take 3 (vec (second %)))

(count (second %))

(count (distinct (second %))))]

(vec (map pf (take 10 (reverse s)))))

;; [["the" ["watery" "world" "spleen"] 13514 4694]

;; [nil ["Call" "Some" "It"] 9854 1763]

;; ["of" ["the" "driving" "every"] 6400 1698]

;; ["and" ["nothing" "see" "regulating"] 5859 2623]

;; ["a" ["little" "way" "damp,"] 4476 2146]

;; ["to" ["interest" "prevent" "get"] 4443 1155]

;; ["in" ["my" "my" "this"] 3796 771]

;; ["that" ["it" "noble" "man"] 2767 975]

;; ["his" ["sword" "deepest" "legs,"] 2414 1281]

;; ["I" ["thought" "would" "have"] 1882 494]]

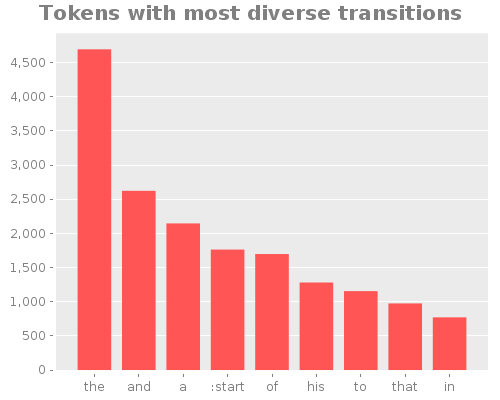

;; tokens with most diverse transitions

(let [cf (comp count distinct second)

s (take 9 (reverse (sort-by cf (vec mc))))]

(view

(bar-chart

(vec (map #(or (first %) :start) s))

(vec (map cf s))

:title "Tokens with most diverse transitions"

:x-label "" :y-label "")))

Generating random sentences

To generate a random sentence, we randomly walk through the markov

chain, starting at nil state, until we hit a terminating token,

which is in our case represented by a keyword. The resulting sequence

of states will be transformed into a string, interposing spaces

between individual words, and ending the sentence with a respective

sentence terminator.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

(defn random-sentence :- String

"Returns a random sentence generated from a given markov-chain."

[markov-chain :- {}]

(let [stop-map {:stop-bang "!" :stop-qmark "?"}]

(loop [sentence [], cur (rand-nth (markov-chain nil))]

(if (keyword? cur)

(str (append (get stop-map cur ".") (interpose " " sentence)))

(recur (conj sentence cur) (rand-nth (markov-chain cur)))))))

(random-sentence mc)

;;=> "I obtain ample vengeance, eternal democracy!"

;;=> "At last degree succeed in the cry."

;;=> "HUZZA PORPOISE."

;;=> "An old, old man, in the bows, at times you say, should be placed as laborers."

;;=> "So, so suddenly started on and strength, let the far fiercer curse the maid."

Summary

We can summarize the whole process as follows.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

(def mc

(->> (slurp (classpath "try/document/moby_dick.txt"))

(tokenizer-engine word-tokenizer)

seq

markov-chain

with-scope))

(random-sentence mc)

The dunaj-project/try.markov repository contains following implementations of markov chains:

-

markov_one.clj- markov chain of order 1, used to generate graph at the beginning of this post -

markov_naive.clj- the relevant source codes for this tutorial -

markov.clj- heavily optimized markov chain of order 2, used to generate sentences for the game below

The program uses latest stable release of Dunaj, criterium, rhizome and incanter. Note that Dunaj works seamlessly with these libraries, and its lite version can be used in cases where the usage of a custom Clojure fork is not possible or desirable.

Guess the novel

Following little game contains selected randomly generated sentences that were generated based on one of the four novels mentioned below. Your task it to guess the source of the text used to construct a markov chain. The text generator used for these sentences is similar to one that was presented here, with some optimizations and bells and whistles added. One notable change is that the markov chain of order 2 was used here, which is a process where the next state depends on the past two states. This results in a less nonsensical text, but needs a fair amount of source data in order to generate unique sentences.

All novels were downloaded from Project Gutenberg. The source code for the generator can be found in the markov.clj file.

This post was published on April 2015. Back to the Blog home

Jozef Wagner

Jozef Wagner